Lessons from the Zong Family’s $1.8 Billion Trust Dispute: Legal and Tax Risks in Cross-Border Asset Planning

In today’s world, where global asset allocation has become the standard for high-net-worth individuals, the cross-border movement of wealth and succession planning face unprecedented complexity.

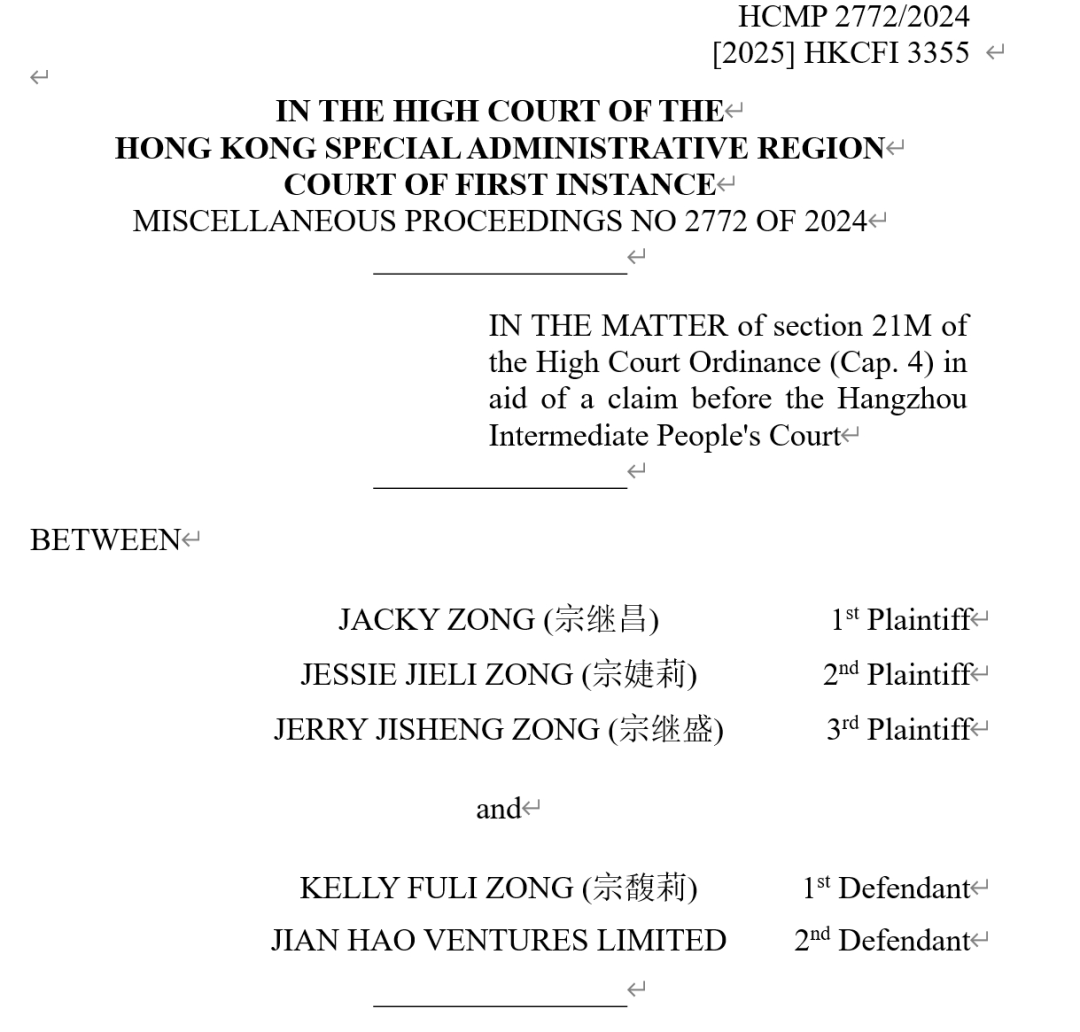

Recently, the $1.8 billion trust dispute involving the family of Zong Qinghou (also known as Zong Senior), founder of Wahaha, has continued to escalate. The case not only involves the inheritance rights of children born out of wedlock but also exposes the legal and tax risks in cross-border asset planning. Such disputes remind us that the globalization of wealth is not a simple matter of diversifying assets—it requires a sophisticated layout across legal, tax, and cultural dimensions.

As a cross-border tax lawyer, I have summarized below the issues most frequently raised by clients, in hopes of clarifying common concerns.

Is a Will Necessary?

Common-law jurisdictions place great emphasis on the freedom of the property owner to make arrangements during their lifetime, while civil-law jurisdictions prioritize the rights of statutory heirs, often including forced heirship rules. Many assume that unless they have complex family situations (such as divorce, remarriage, or children out of wedlock), they can simply rely on their country’s intestacy laws. But intestacy often leads to outcomes contrary to personal intent.

For example, under China’s intestacy laws, a spouse, children, and parents are all first-tier heirs and inherit equally. In U.S. community property states (e.g., California), the surviving spouse inherits all community property, regardless of whether there are children.

For those holding assets in multiple jurisdictions, the key issue is whether intestacy laws of the asset’s location or the decedent’s domicile apply. China and California both apply local intestacy laws for real property located within their borders, but for personal property, the decedent’s domicile laws generally apply.

In Zong Senior’s case, he resided long-term in Hangzhou before his death. The three plaintiffs were children born out of wedlock, and under Chinese law, they have equal inheritance rights to legitimate children. Zong Senior had executed two wills—one in China for his domestic assets, and another offshore for his foreign assets. The disputed assets were mainly movable property in Hong Kong, including HSBC accounts held by a BVI company. Since Hong Kong follows common law and Zong Senior had a valid will, the plaintiffs’ inheritance rights were not in dispute.

One Will or Multiple Wills?

High-net-worth individuals with multinational assets face multiple legal systems. Many families already understand the importance of a will to maintain control over asset distribution. However, a single will may face challenges abroad:

Forced heirship rules in civil-law countries may override testamentary freedom.

Formal validity issues may render a will ineffective abroad. For example, some U.S. states do not recognize holographic (handwritten) wills, even with witnesses.

If a local court invalidates the will, intestacy rules apply.

Alternatively, drafting separate wills for each jurisdiction may create conflicts. Common-law wills often include “catch-all” clauses, and depending on timing, a new will may unintentionally revoke prior ones.

Additionally, in common-law countries, wills typically require probate. In the U.S., unless assets are held in trust, probate is unavoidable. Probate courts verify the will’s validity, disclose its contents publicly, and allow creditors or heirs to contest. If estate tax is involved, the IRS requires tax clearance before distribution. The process may last years, draining time and resources.

Thus, even when wills are valid, execution may be long and costly. More families, like the Zongs, adopt multiple wills (e.g., a China will plus an offshore will). But even then, disputes can drag wills into court, exposing private family and financial details and harming the family’s overall economic interests.

Lifetime Trust or Testamentary Trust?

According to the Hong Kong court’s analysis, Zong Senior had instructed his daughter Kelly Zong to establish three offshore trusts (one for each plaintiff), each with $700 million, funded by assets held in a wholly-owned BVI company’s HSBC Hong Kong account.

He specified:

The trusts must be irrevocable.

Beneficiaries were the plaintiffs and their descendants.

Trustees could distribute only trust income, not principal.

A PTC (Private Trust Company) would serve as the initial trustee before professional trustees assumed management.

This arrangement meant the trusts would be created after Zong Senior’s death—so-called testamentary trusts—rather than inter vivos (lifetime) trusts.

Since Kelly Zong did not establish or fund the trusts before litigation, she continued to control the assets via her BVI company. The Hong Kong court therefore froze the assets temporarily to protect the plaintiffs.

This case highlights the risks of testamentary trusts: their creation depends entirely on executors or fiduciaries after death, leaving beneficiaries exposed. Litigation is often the only way to enforce rights.

Historically, trusts arose in medieval England, when knights entrusted land to others while on crusade. Courts of equity required trustees to act loyally for beneficiaries, prohibiting conflicts of interest. That fiduciary duty remains the cornerstone of trust law today.

In the Zong’s case, Kelly’s insistence that her descendants should be added as beneficiaries presented a clear conflict of interest and breach of fiduciary duty.

Revocable vs. Irrevocable Trusts

Zong Senior’s instructions specified irrevocable offshore trusts for the plaintiffs.

Revocable Trusts: The settlor retains the power to amend or revoke.

Irrevocable Trusts: Cannot be unilaterally revoked by the settlor, though modern structures often permit limited modifications by trustees or protectors, provided beneficiaries are not harmed.

In practice, irrevocable trusts are often used for tax planning or shifting jurisdiction. The Zong’s dispute underscores the risks of relying on executors or fiduciaries to implement trust arrangements after death.

U.S. Estate and Gift Tax Considerations

The Zong’s case did not involve estate tax, but families with U.S. assets must plan carefully. Unless there is a bilateral estate tax treaty, executors may need to file in both jurisdictions, pay taxes, and later seek refunds—creating a risk of double taxation.

The proposed “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) provides that starting January 1, 2026, the unified U.S. exemption for estate, gift, and GST (generation-skipping transfer) tax will be permanently raised to $15 million per individual ($30 million per couple), indexed annually by ~2%. The 40% tax rate above this threshold remains. This replaces the prior law under which exemptions were set to fall back to ~$6.8 million in 2026.

However, non-U.S. persons with U.S. situs assets remain subject to a mere $60,000 exemption—leaving foreign investors exposed to potentially catastrophic U.S. estate tax liabilities.

Conclusion

The Zong family’s $1.8 billion trust dispute offers a cautionary tale:

Wills must be carefully structured for multiple jurisdictions.

Lifetime trusts often provide stronger protection than testamentary trusts.

Fiduciary duties must be enforced to avoid conflicts.

U.S. estate tax planning is essential for global families.

Cross-border wealth planning requires more than asset diversification—it demands precise, multi-dimensional legal and tax strategies.